Where does sugar come from?

Sugar's story starts in the field.

Learn MoreWhile chewing sugar cane for its sweet taste was likely done in prehistory, the first indications of the domestication of sugar cane were around 8000 BCE. Follow sugar’s historical journey across the world and the advances in technology that allow us to enjoy sugar today.

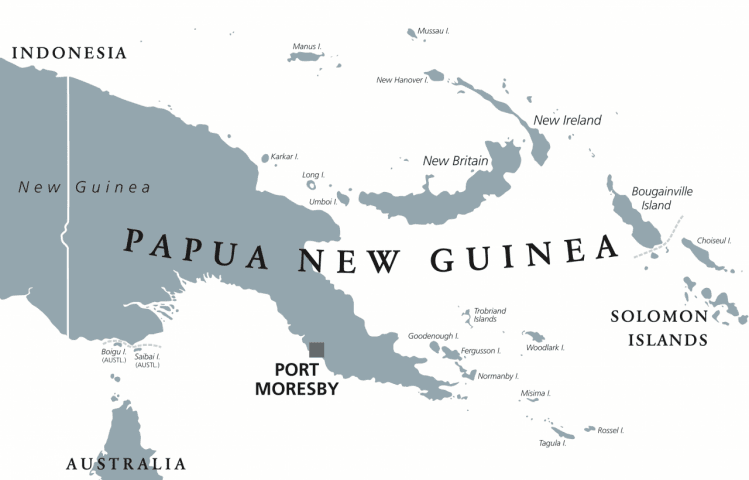

First probable domestication of sugar cane by the indigenous people of New Guinea, who chewed it raw.1

Sugar cane cultivation practices spread throughout Southeast Asia, China and India via seaborne traders.2

Crystallized sugar was found in medicinal records of both Roman and Greek civilizations; it was used to treat indigestion and stomach ailments.3

Sugar crystallized in India for the first during the Gupta dynasty.4

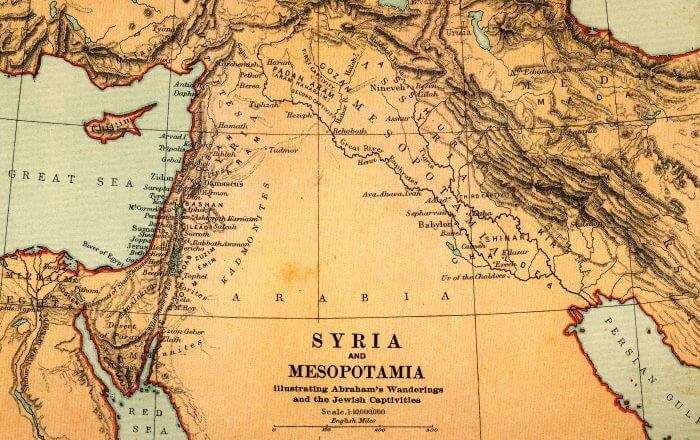

Sugar cultivation and processing methods reached Persia; techniques were spread into the Mediterranean by Persian expansion throughout Mesopotamia.5

China developed its first sugar cane cultivation techniques using technology acquired from India.6

Sugar cane was grown extensively in Southern Europe following the Persian conquest of the region; it was primarily grown in Sicily and Spain.7

Sugar cane cultivation practices spread to the Eastern Mediterranean (Cyprus) and East Africa (Zanzibar).8

Crusaders returned to Europe from the Holy Land with prizes of sugar, called “sweet salt”.9

Lebanese land estates near Tyre were established to grow sugar cane and export it to Europe.10

Advanced sugar presses were developed, doubling the amount of juice that was obtained from the sugar cane.11

Sugar was cultivated for large-scale refinement for the first time in Madeira; by the end of this period, about 70 ships were involved in the Madeira sugar trade, and refining and distribution were based in Antwerp.12,13

The Portuguese brought sugar to the New World (Brazil).14

Hispaniola (Haiti/Dominican Republic) had its first sugar harvest.15

800 sugar cane mills were developed on Santa Catarina Island, along with another 2,000 mills along the north coast of Brazil.15

Approximately 3,000 sugar mills were built in the Caribbean and South America.15

Dutch colonists introduced sugar cane to South America and the Caribbean (Barbados, Virgin Islands).16

Sugar became an extremely popular commodity, representing 20% of all European imports; toward the end of the century, the British and French colonies in the West Indies produced 80% of the sugar.17

German chemist Andreas Marggraf identified sugar in beet roots.18

Sugar cane was brought to Louisiana, making it the final sugar colony.1

The first steam-powered sugar mill was constructed in Jamaica.19

Marggraf’s apprentice, Franz Karl Achard, built Poland’s first sugar beet processing facility.20

Edward Charles Howard invented a more fuel-efficient method of refining sugar, which boiled the cane juice in a closed kettle heated by steam and held under partial vacuum; it was called “Howard’s vacuum pan.”21

David Lee Child built the first U.S. sugar beet factory which was in Northhampton, Massachusetts.22

Cuba became the richest land in the Caribbean; it was the only major island free of mountainous terrain and ideal for sugar cane production.23

David Weston became the first to use Hawaiian centrifuges to separate sugar from molasses.24

The first successful commercial sugar beet production in the U.S. began in central California. By 1890, sugar beet factories were established in Watsonville and Alvarado.25

In Peru, W.R. Grace Company developed the first industrial-scale conversion of bagasse into paper.26

The mechanization of sugar cane cultivation began when 16 whole stalk harvesters were successfully used to harvest cane in Louisiana in 1938, and by 1946 (because of wartime labor shortages), 422 whole stalk machines cut 63% of the crop in Louisiana.27

The Sugar Research Foundation patented colorless sterile invert sugar.28

The first bagasse diffuser, based on the existing technology of Egyptian diffusers, was installed in South Africa.29

December 12, 2016 marked the last sugar harvest in Maui. After more than a century, Hawaii will no longer produce sugar.

Sugar beet and sugar cane yields continue to improve with modern varieties of the plants and advances in agricultural technology.

1. Noël Deerr, The History of Sugar: Volume One (London: Chapman and Hall, Ltd., 1949), 15.

2. “SKIL- History of Sugar,” Accessed March 7, 2018, http://www.sucrose.com/lhist.html.

3. Dioscorides, De Materia Medica: Book Two (50-70).

4. Michael Adas, Agricultural and Pastoral Societies in Ancient and Classical History, (Philadelphia, Temple University Press, 2001), 2341.

5. Matthew Parker, The Sugar Barons: Family, Corruption, Empire and War (London: Hutchinson, 2011), 10.

6. John Kieschnick, The Impact of Buddhism on Chinese Material Culture (Princeton: University Press, 2003).

7. Robert Gangi, “Sugar Cane in Sicily,” Best of Sicily Magazine, 2004. Accessed March 8, 2018, http://www.bestofsicily.com/mag/art143.htm.

8. Clive Ponting, World History: A New Perspective (London: Chatto & Windus, 2000), 353.

9. “History of Sugar,” Accessed March 8, 2018, http://www.sugarhistory.net/who-made-sugar/history-of-sugar/.

10. Clive Ponting, World History: A New Perspective (London: Chatto & Windus, 2000), 481.

11. Ann Pearlman, The Christmas Cookie Club: A Novel (Simon and Schuster, 2009), 234.

12. Noël Deerr, The History of Sugar: Volume One (London: Chapman and Hall, Ltd., 1949), 100.

13. Clive Ponting, World History: A New Perspective (London: Chatto & Windus, 2000), 482.

14. Noël Deerr, The History of Sugar: Volume One (London: Chapman and Hall, Ltd., 1949), 102-4.

15. Antonio Benitez-Rojo, The Repeating Island (Durham: Duke University Press, 1996), 93.

16. Noël Deerr, The History of Sugar: Volume One (London: Chapman and Hall, Ltd., 1949), 208.

17. Clive Ponting, World History: A New Perspective (London: Chatto & Windus, 2000), 510.

18. Andreas Marggraf, “Experiences chimiques faites dans le dessein de tirer un veritable sucre de diverses plantes, qui croissant dans nos contrees,” Histoire de l’academie royale des sciences et belles-lettres de Berlin, 1747. 79-90.

19. Vermont M. Satchell, “Early Use of Steam Power in the Jamaican Sugar Industry, 1768-1810,” Transactions of the Newcomen Society, 67:1, 2014. 221-231.

20. Zuckerfabriken Schlesien, Handbuch der Politischen Oekonomie, 1896. 80.

21. Frederick Kurzer, “The Life and Work of Edward Charles Howard,” Annals of Science 56:2, 1999. 113-141. Accessed March 10, 2018, https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/000337999296445.

22. Austin, Harry. History and Development of the Beet Sugar Industry. National Press Building, Washington D.C. 1928.

23. Clive Ponting, World History: A New Perspective (London: Chatto & Windus, 2000), 698-9.

24. “US Grant US236389A”, Accessed March 6, 2018, https://patents.google.com/patent/US236389.

25. Robert M. Harveson, “History of Sugarbeets,” Accessed June 18, 2018, https://cropwatch.unl.edu/history-sugarbeets.

26. Lawrence Clayton, Grace: W.R. Grace & Co., the Formative Years, 1850-1930 (Ottawa, IL: Jameson Books, 1985), 354.

27. Geoff Burrows and Ralph Shlomowitz, “The Lag in the Mechanization of the Sugarcane Harvest: Some Comparative Perspectives,” Agricultural History 66, no. 3 (1992): 69. http://www.jstor.org.mutex.gmu.edu/stable/3744501.

28. “US Grant US2758040A,” Accessed June 18, 2018, https://patents.google.com/patent/US2758040A/en.

29. I. Voigt, “The Implementation of South African Sugar Technology: The World’s Largest Sugarcane Diffusers,” South African Sugar Technologists’ Association 82 (2009): 270. https://www.sasta.co.za/wp-content/uploads/Proceedings/2000s/2009%20Voigt.pdf.

You may have heard the term “sucrose” at one point or another—but what is that, really?

Learn More© 2025 The Sugar Association, Inc. All rights reserved.

Get Social with #MoreToSugar